Meet my friend Matt — astrophysicist, cosmologist, DJ, sky diver, paraglider, lucid dreamer, and graffiti artist — to name just a few things.

I recently asked him some questions after watching a documentary about the multiverse that really blew my mind and confused me at the same time.

QUESTION: Are there really multiple separate universes or multiple universes within the one universe? What exactly is the multiverse?

The question of the multiverse is one that is so often misrepresented in the media and even in some arenas that you would expect to take a little more care with such things.

The theory I favour when talking about this subject is a model proposed by Max Tegmark. The reason I like this model is two-fold.

Max Tegmark’s multiverse theory

Firstly, Tegmark’s model came about after analysis of astronomical data. This means it isn’t pure speculation, in fact, I don’t believe he was looking for a theory of the multiverse at all from this data, but rather that the data pointed him towards a multiverse.

Secondly, Tegmark’s model consists of four levels: the first two deal with large scale perturbations in space that arise as a consequence of the Big Bang. The upper two levels (if there was such hierarchy), consider the micro-scale perturbations that arise from increasingly complex consequences of quantum mechanics.

With each level we are presented with an increasingly mathematical and controversial landscape and it is this aspect that, with the level four multiverse, really divides the Platonists from the Aristotleans — but we’ll come to that.

Let’s start with two assumptions that are used and verified through observational data and which underpin the Multiverse theory.

- Space is infinitely or at least sufficiently large.

- The Universe has a generally uniform distribution of matter.

The first one of these assumptions is of course difficult enough to rationalise. So, to make it less complex, we’ll start by looking at the speed of light.

The speed of light explained

It has been (by our current estimates) 14 billion years since expansion happened after the Big Bang. With light travelling at a speed of approximately 300,000,000 meters every second, we can do some simple maths and work out that light travels a distance of approximately:

(300,000,000m x 60s x 60min x 24 hours x 365 Days) = 9,460,800,000,000,000m a year.

That’s Nine Quadrillion, Four Hundred and Sixty Trillion, eight hundred billion metres each year!

For ease of use, we call 9,460,800,000,000,000m a light year: the distance that light from luminous sources in space can travel in one year.

This means that each year, light from increasingly distant objects has the time to reach us. So we can say that our observable universe, (or Cosmic Horizon), increases in size by a light year each year.

Level 1 multiverse

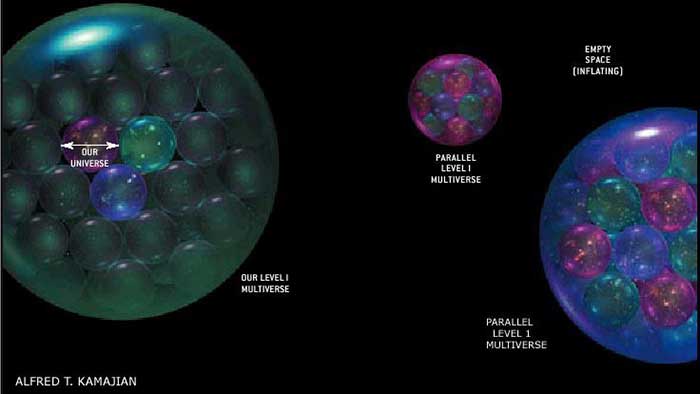

In the level one multiverse, the vastness of space allows for there to be enough room for multiple universes to exist within that space, just too far away from us to be observable yet — in other words beyond our cosmic horizon. We can imagine each universe then as a bubble with a planet with observes on it at the centre.

Currently we can ‘see’ back 42 billion light years. This is greater than the 14 billion years quoted as the age of our universe you might notice, but that’s due to cosmic expansion, which has lengthened distances. So it is possible with enough time (not in our lifetime), that future generations could observe another universe using the most advanced (probably space-based) telescope of the age.

That universe wouldn’t be an identical parallel universe, but simply a universe with differing arrangements of matter that formed it. All of the universes in this level one multiverse would still, however, abide by the laws of physics that are our own.

The nearly uniform distribution of matter and one part per 100,000 initial density distribution are ‘normal’ conditions in any possible universe that contains observers. This confidence in the model came from WMAP and the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey, which confirmed that space on large scales is filled with matter uniformly, meaning that other universes should look basically like ours.

Based on this estimate your closest identical copy is 10 to the 10118 meters away. So you don’t have to worry about a non-time travel related ‘back to the future’ style doppelgänger annihilation scenario — not only because of the distances involved, but also because if the expansion of space is accelerating as we believe it to be, then the distances between universes would continue to increase, thus rendering us isolated in our level one multiverse forever.

Level 2 multiverse

The level two multiverse takes this idea of a vast array of universes all inhabiting the same space and essentially not only postulates how these might have come about, but also answers the all too glaring question of what lies outside of this space?

This multiverse is a consequence of inflation theory which in itself explains why the universe is so large, uniform and so flat. The idea is that space rapidly expanded after the Big Bang and it’s this rapidity of the stretching of space that can explain all the attributes above.

Space, (which remember we said was considered to be infinite or at least extremely large), is stretching on an infinite time-scale. However, some localised regions of space stop stretching, due to equalised forces acting on them from the wider spacial region and the dispersement of the energy field that drove inflation in the first place.

If the story ended there then we would just find static flat regions of space amongst the remaining stretching space. But due to the energy field that drove inflation in the first place, these regions become filled with matter and expand like those formed on the skin of rice-pudding or soup when it is simmering.

Each of the bubbles created would be a level one multiverse in the making and even if we travelled from Earth forever at the speed of light, we would never reach our nearest neighbouring level one multiverse, because the space between our bubble and the neighbouring one is expanding faster than we could travel across the space itself, thus meaning we would never meet our doppelgänger at all.

These distinct bubbles that we call the level two multiverse, contain an infinite number of universes as in level one, but this time, the physics governing each level two multiverse might not be the same. It is thought that the symmetry break was responsible for creating everything that we see in our universe; from the number of dimensions to the physical-constants that we hold as being set in stone.

The symmetry break came about as a direct consequence of inflation and we know that there were chaotic quantum fluctuations that drove this inflation in our universe, meaning that the likelihood that these exact conditions would be replicated in another level two multiverse are nil: each level two multiverse would be unique!

There’s a similar theory to this level two multiverse, which involves membranes or branes. It sought to solve the mystery of what caused the Big Bang. These membranes are four-dimensional bubbles, which wander around in the space they occupy. When two of these branes collide, they begin to pass through one another. The cross-section of a four-dimensional object would be a three-dimensional object.

So the cross-section of the four-dimensional bubble would be a three-dimensional sphere. The theory states that at the point the two branes touched, our three-dimensional universe began. As an observer inside the membranes, at this point you would observe a ‘something-out-of-nothing’ scenario as a point appears seemingly from out of nothing and begins to expand into a 3-D universe before your very eyes.

Inevitably, because the membranes are passing through one another, there would come a point of a ‘Big Crunch’ scenario, as our universe began to collapse in on itself due to the membranes passing out of each other.

Level 3 Multiverse

So far we’ve discussed multiverses that occur in realms that are tangible to our minds but never to our vision. Now, however, we delve into a multiverse that is perhaps the most difficult to fathom.

By the end of the 19th Century, we had made headway into unlocking the secrets of the atom, but the general consensus still rested on the assumption that the machinations of the micro-world mimicked the Newtonian mechanical systems of the macro-world of the heavens.

Even in school today, the starting point for atomic theory consists of a model of electrons orbiting a central nucleus. It’s no coincidence that this rudimentary system looks similar to our Earth-Moon system. This was the accepted Newtonian model of the day.

In the early 20th century, quantum mechanics turned that realm on its head, as it could now fully explain a world which Newtonian mechanics could not. This required, however, a change in our notions of certainty.

This new realm defined our universe, not in terms of the positions and velocities of particles, for example, but using de Broglie’s idea that each particle had an associated wave-like character. Erwin Schrodinger would later take on this idea and develop it further to create wave functions.

Thus, having harboured on the shores of this newly discovered land, we find that the universe is described in terms of these wave functions. A wave function defines the probability of an outcome of an event, in a mathematical manner. It doesn’t predict the outcome explicitly, but will yield a distribution of outcomes based on their probability. So these wave functions can be thought of as probability functions of one specific outcome or another.

A mathematical space of abstraction & Schrödinger’s cat

These wave functions evolve over time in what physicists call a unitary fashion. This means that the wave function rotates in an abstract infinite-dimensional space. Just to be clear here, this isn’t space like that stuff the Earth sits in, but a mathematical space of abstraction. This space is called Hilbert Space and as it turns out, the wave function evolves in a very deterministic way in this space.

The problem comes when we try and marry these wave functions to the observations that we make. The classic example in the general psyche, is the example of Schrödinger’s cat. In Schrödinger’s now famous thought experiment the cat in the box is both dead and alive at the same time.

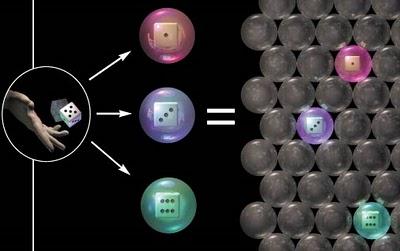

This notion of occupying multiple states at the same time, we call Superposition. The current thinking suggests that one classical reality gradually splits into superpositions of many realities, where the only noticeable aftershock the observers subjectively experience would be a bit of randomness.

This superposition of classical worlds is the level three multiverse and it exists all around us.

What are the real world implications of this?

It means that if you throw a six-sided die and it lands on the number three in this universe, at that very same instant due to quantum effects in their brain (Something that I’ll talk about in a later article), the classical world splits into six other superposition realities. In each of these, the die lands on a different number and in the last, you decide not to throw the die at all.

So if you wished that you had taken that job you turned down or given up yours to go and live in a van you converted yourself, rest assured that in another universe somewhere around you in Hilbert Space, you have!

This means the Buddhists were right when they said that consciousness creates reality in this level three multiverse.

The stranger part perhaps is that this same outcome also occurs in the level one multiverse. The only difference between the level one and level three multiverse is the location of your doppelgänger. In the level one multiverse it is in other regions of three-dimensional space too far away to be observed. In the level three multiverse it’s on one of the other quantum branches of the infinitely dimensional Hilbert Space.

This immediately seems incredibly implausible to us as we go about our daily business. But as I’m always telling my students, it’s a matter of reference frame. We can study a physical system from outside of itself, or from inside where, in this case, we reside.

That’s the difference between the POV camera mounted on the helmet of a big mountain snowboarder as they plummet down a 60° face and the automated drone footage from above. Each gives a different perspective of the ride down the mountain, most annoyingly, from experience is the inability of the POV camera to capture the severity of the incline of the slope. Something that is all to evident from the Automated drone’s perspective.

Even though both perspectives show the same event, it would be incredibly difficult for us to imagine the automated drone’s viewpoint during the event, as it would be the drone to perceive the height variations experienced by the POV wearer as they plummet off that cliff half-way down the run.

You might assume that as the levels progress they become increasingly unlikely. However, as long as the evolution of the wave function over time is unitary, then all three levels of multiverse are probable. This time-based evolution of the wave-function has been proven on what might even be considered ‘large’ scales, such as kilometre long optical fibres. So for now at least we should get used to the idea of being surrounded by self.

The interesting caveat for me and an aspect of this multiverse system that I’m currently developing methodologies to explore, is the idea of the slight randomness that arises when the classical reality splits. The question I’m interested in is what exactly we notice when this randomness happens. Is it definable such that we consciously discern when our classical reality is breaking down into quantum worlds?

Level 4 multiverse

I’ll only mention the level four multiverse briefly here, as I believe that there are too many avenues to explore to be useful, as there are few constraints which limit the outcome of this multiverse.

In the level one to three multiverse, although the initial conditions and physical constants can vary, the fundamental axioms that govern the natural laws remain constant. Here in the level four multiverse, we assume that these fundamental axioms to, can vary.

Thus producing innumerable universes that could range from those where classical mechanics reigns supreme, one where quantum effects never came about, to ones populated purely by dark matter, in which ordinary matter is the exotic material.

The reason that we can even begin to postulate about these universes in level four at all is remarkable and although usually reserved for the kinds of late night tea-drinking conversations amongst friends, there is some basis to such postulations.

This brings me back to a point I made at the beginning of the article regarding Aristotle and Plato. We might not give it much thought or ascribe to it consciously, but the majority of us are in fact Aristotelian thinkers.

Aristotle and Plato

Anyone who has tried explaining to their engineering parent why they have chosen to go and study some form of theoretical physics at university might have run into this type of Aristotelian thinking.

Aristotle believed that Mathematics was merely a language that was useful for describing the universe, but was not the universe itself. Much as poets or artists might use language or oils to describe a sunset atop a misty Tor, no matter the skill of the artist, their best efforts will never yield the reality of the sunset itself. Or so the Aristotelian paradigm would assert.

The Platonists on the other hand, would regard mathematics as ‘nature lain bare’. To them, mathematics is the purest form of the expression of the universe. It is our perception of nature which distils it down to a mere interpretation of the reality of what we see around us: that governs us.

To the Platonist mind, the very fact that we can take a mathematical equation and apply it directly to the world around us suggest that the universe itself must be inherently mathematical. Thus the more mathematics describes this universe correctly, the more the Platonists suspicions are confirmed.

This then renders the universe and subsequently, all multiverses simply a mathematical problem to be solved like any other. As a physicist, this has never sat with me very comfortably. Although I would not consider myself an Aristotelian by means, I believe that outsourcing all these types of problems to mathematicians is a problem.

Again, one of the reasons that I prefer Tegmark’s analysis of this Multiverse, despite him being initially a mathematician, is because he does regard the physical data and understands the physics behind this data in order to produce a theory which nicely straddles the two disciplines.

It’s easy to get to the end of an article like this, give these notions a further two minutes of thought and then go back to doing whatever it was that preceded this interlude. Conversely it’s tricky as the author to bring this into some sort of real World context when actually we’re talking about the greater context beyond our perceptible consciousness.

So the message I’d like you to take away from this article is that our reality is untethered to our narrow focus, potentially unbounded and although we are faced with too many other Earthly concerns, there is room to consider these wider aspects even if we cannot fully comprehend them. Because, only through consideration and mental exploration can we build from where we are to a future without obstacles to betterment.

Written by astrophysicist and cosmologist Dr Matt Brown

October 2021 Update

Check out Matt’s podcast here on the Squiggly Lives Podcast