Yoga’s history has fascinated me for a long time and I’m writing this post because I know a lot of yoga practitioners are interested in this too.

I felt inspired to share this post because I was recently asked to do a short online workshop which would include talking about the origins and history of yoga and how that relates to yoga today. Although the history of yoga absolutely fascinates me, I just felt I knew nowhere near enough to do this justice.

The truth is that even on my yoga teacher trainings, there is a huge chunk of yoga’s history missed out — at least this was the case with me. So, what I’m going to share with you is an essay I wrote for the the History of Yoga online course that I did with the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies.

Please don’t take me as an expert though (I’m still learning a lot). It was something I wrote whilst doing the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies’ course on the History of Yoga: Medieval to Modern (please note that I am not affiliated in any way, I was simply a student of this course) and thought it might interest others too rather than it just sitting on my hard drive doing nothing.

I’ve included book references at the bottom, but one book in particular which I highly recommend is Yoga Body by Mark Singleton. I also highly recommend the course I did too if you are interested in learning more about yoga’s history from people who are actively researching the subject.

I won’t share the essays title as I’m I’m not sure if it’s still being used as the main assignment but it discusses the history of modern and premodern Hatha Yoga.

My essay on modern and premodern Hatha yoga

In the book Roots of Yoga, Mallinson argues that premodern yoga can be identified through breath control, whereas, yoga today is identified through bodily postures. (Mallinson 2016) What, therefore, is the story that changed the identifying features from breath control in premodern hatha yoga to an emphasis on the physical body in 20th century modern yoga?

This shift from breath to body appears to have taken place during the British colonial period of the 19th and 20th centuries which I will be referring to as the modern era, and for the purpose of this essay, I will be defining the premodern period from the 15th century, just after the publication of the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā.

Premodern hatha yoga and the breath

The Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā is a compilation of what could have been as many as 20 other works, that were combined to produce a clear system of hatha yoga for practitioners to follow. The text states in the translation that ‘it is through breath retention that hatha is mastered’, reinforcing the idea that breath control was important during the premodern period.

I’m not going to list all the exercises outlined in the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā, but I will highlight that some of the pranayama exercises detailed also play a prominent role in some of the modern yoga practices. For example, the Ujjayi breath in Pattabhi Jois’s Ashtanga yoga, and Kapalabhatih and Analoma Viloma in modern Sivananda Yoga.

Similarly, the 15 asanas, outlined in the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā also feature across different disciplines of modern yoga. However, the very fact that there were only 15 asanas listed here, compared to the asana heavy practices of the modern period, suggests that the focus was not on achieving perfection in physical postures in their own right. The Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā supports this point by saying ‘Hatha yoga is the practical way to control the mind through control of the prana’. It could, therefore be suggested thatasanas were used as a tool for a higher purpose.

Although the asanas listed, feature in modern yoga practices, linked repeated sequences don’t make an appearance until the 18th century, and yoga’s ‘famous’ Surya Namaskara or the Sun Salutation, is very much a construct of the modern period. Physical exercises in the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā tended to focus on floor based asanas and inversions. There are virtually no standing poses. The closest comparison I can draw here to the modern practices of yoga is that of the Sivananda method systematised by Swami Vishnudevananda. Similar to the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā, the sequence practised focuses on longer holds of asanas that are mainly inversions with other seated asanas.

Another key feature of the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā was that it was the first text to list the therapeutic benefits of hatha yoga, with many of these feeling timeless. For example, the following description is used for the headstand: ‘After six months of regular practice wrinkles and grey hair disappear.’ This could almost read as a 20th century advert – aimed at any modern image concerned person – for a revolutionary anti ageing product!

Perhaps it could be argued that listing the therapeutic benefits throughout the text, helped it to stand the test of time, making it relatable to modern western minds. Focusing on the benefits that could be easily understood and associated with the physical body and material world, turns yoga into a practice that’s easily accessible, as opposed to only focusing on the benefits or outcomes that cannot easily be seen or that are not part of the material world.

The Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā was also the first yoga text not to be attributed to a God or human worshipped as a God. Could the non-sectarian nature of this text be another reason it was still accepted and used in practice in the modern period? We know that during the end of the 19th century, the yogi, Vivekanada, who I will be discussing further on in this essay, was successful in promoting yoga to a global audience partly because he was a clear communicator, and able to tailor his arguments using language that could be understood by predominantly western Christian audiences.

Colonial India and the change in the perception of yoga

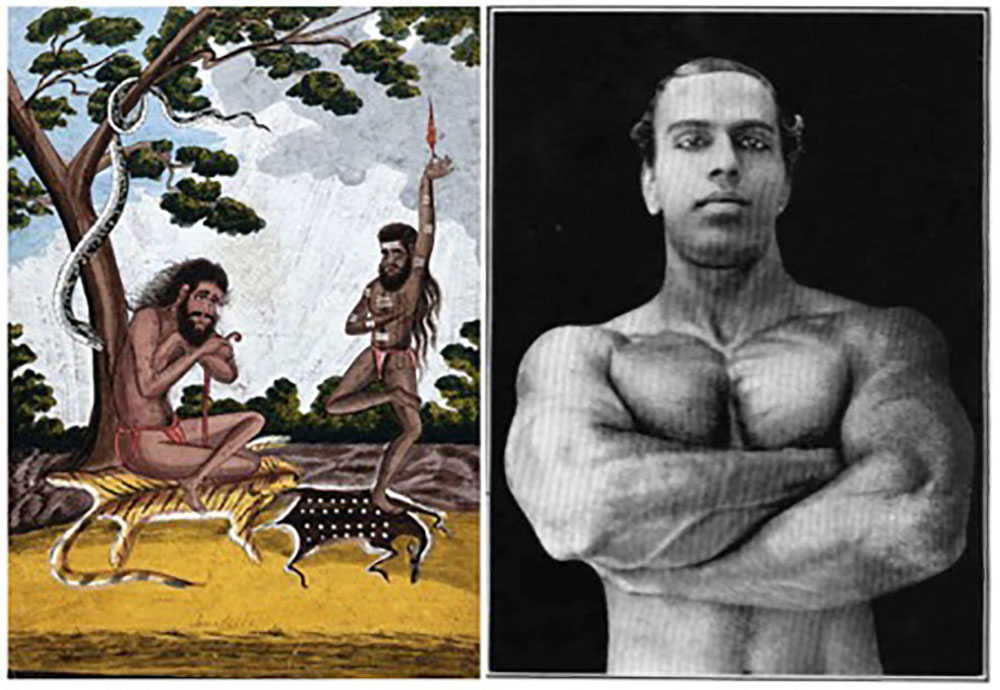

Up until the 18th Century, hatha yoga had flourished in India since the publication of the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā. However, during the British rule of India, hatha yoga started to conjur up negative connotations. The British created illustrated documents depicting yogis as non-conformist ascetics, magicians and freaks, who reflected negatively on the rest of the Indian nation. Under this ‘colonial gaze’, all yogis or ‘jogis’ were identified as being just one group.

To further illustrate the negative perception of yoga in India during the time of British rule, I’m going to quote one of modern yoga’s prominent figures, B.K.S Iyengar, from his book Light on Life:

‘I set off in yoga seventy years ago when ridicule, rejection, and outright condemnation were the lot of a seeker through yoga even in its native land of India. Indeed, if I had become a sadhu, a mendicant holy man, wandering the great trunk roads of British India, begging bowl in hand, I would have met with less derision and won more respect.’ (Iyengar 2005)

How, therefore, in a matter of decades, was yoga transformed into the global phenomenon of the 20th century, now labelled ‘modern yoga’, identified through its emphasis on bodily physical postures?

One of the key figures to instigate this global transmission of yoga was Swami Vivekananda, who delivered his first speech in 1893 on Hinduism and Yoga in the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. This is interesting because although he tailored his talks for a western Christian audience, he omitted hatha yoga and any mention of asana – preferring instead to focus on the following four yogas: karma (selfless service), bhakti (devotion), raja (the royal path), and jnana (knowledge) yoga, which are prominent in the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā and also modern Sivananda yoga.

In his attempt to portray yoga in a more positive light on a global level, Vivekananda set about rebranding yoga as a universal, non-sectarian philosophy, sharing just a taster of what yoga is, and adding his own thoughts. He made comparisons to western scientific theories and also described elements of yoga philosophy in a suitably tailored way for western Christian audiences, such as using the word soul as a translation for the sanskrit term Atman.

It could therefore be argued that Vivekanada’s views helped to change the perception of yoga away from the British image of a magical circus freak show, not worthy of respect. You could say, Vivekananda was a skilled marketer, speaking the language of his audiences in order to sell them his version of yoga, using funds from his talks abroad to help fund India’s Nationalist mission.

Modern yoga and the emphasis on bodily posture

Yoga plays a big part in Indian Nationalist’s mission for an Independent India, which involved creating a united nation made up of people who were physically strong and healthy, who could fight for the vision of political independence.

What emerges from this era is a massive east-west fusion of ideas and physical practices, popular in the 19th century, from Indian wrestling to Swedish gymnastics. Driven by the Christian ideology that ‘bodily strength and health presupposed moral vigour’ (Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies course manual), emphasis on the body and the importance of physical exercise became incredibly popular. These individual practices were grouped and termed ‘physical culture’ which made its way into mainstream society where it then fused with Indian physical culture practices such as wrestling and the asana practices of hatha yoga.

This fusion of eastern and western physical practices and emphasis on the body was in alignment with the Indian Nationalist’s mission. Although on the surface, it might look like asanas are being used to create a superficial six pack nation, just like the practice of hatha yoga in the premodern period, weren’t asanas being used here to serve a greater or higher purpose too – only this time to fight for political independence and unite a nation?

One of the key bodies of physical culture was K.V Iyer who wrote Muscle Cult, which advocated his fusion of bodybuilding and asana practice through photography. This image portrayed in Muscle Cult seems worlds apart from those early illustrated documents created by the British, depicting yogis as magicians and circus freaks. Modern yoga, therefore, is very much the product of this body orientated physical culture, but as I highlighted earlier, it is not completely severed from its premodern roots.

The 20th century is host to a wide range of gurus creating their own versions of yoga. Some of the key figures include Tirumalai Krishnamacharya whose students were Pattabhi Jois, and B.K.S Iyengar. Both Jois and Iyengar, went on to create their own systems of yoga identified through bodily postures, which include many more asanas than the 15 originally outlined in the Hatha Yoga Pradīpika.

Another key figure in modern yoga was Swami Sivananda, who although unlike Vivekanada, advocated hatha yoga, he also adopted many of Vivekanada’s ideas. For example, although physical postures feature heavily in Sivananda yoga, this style of yoga also places breath control very literally at the start of the physical Sivananda sequence in that it opens with the practices of Kapalabhatih and Analoma Viloma, which follow the teachings of the Hatha Yoga Pradīpika pretty accurately. Sivananda yoga also incorporates the four yogas promoted by Vivekanada, mentioned earlier in this essay.

Conclusion

‘Has the ancient science of yoga any worthwhile place in the life of the modern man? (Yogananda 1946)

Modern yogi Paramahansa Yogananda poses the question ‘Has the ancient science of yoga any worthwhile place in the life of the modern man?’ (Yogananda 1946)

at the start of his book Autobiography of a Yogi, affirming that after receiving thousands of letters from readers, the west has found an answer to this question.

After viewing key developments and relationships in the history of yoga, we can answer the same question too in the context of yoga’s purpose, importance and ‘worthwhile place’ in modern and contemporary society. Modern yoga, despite appearing outwardly different from its premodern hatha roots, has probably and will likely play an even more important role in not just the lives of individual practitioners of yoga, but in uniting societies as a whole, connecting religions, and blurring boundaries that lead to divisions in the world.

Ultimately yoga seems to do a great job in tailoring its practices or entryways in order to be inclusive, and is unafraid of change when it comes to its outward expression. This is in pursuit of serving a mission higher than any of its identifiable features of body, breath control… or any label for that matter. The body, the breath, the six packs of ‘physical culture’ – are all tools for an outcome that aims to transcend boundaries and be in search of something much greater than the methods used to get there.

References

(Books referred to outside of the History of Yoga course videos, manual, and forum)

Feurstein, G. (2001). The Yoga Tradition. Arizona: Hohm Press.

History of Yoga. (n.d.). Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies.

Iyengar, B. (2005). Light on Yoga. London: Rosdale Pan Macmillan, p.xiii.

Mallinson, J. and Singleton, M. (2016). Roots of yoga. Penguin.

Vishnudevananda, S. (2016). Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā. 3rd ed. Delhi: Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centre, p.3.

Yogananda, P. (1946). Autobiography of a Yogi. 13th ed. Los Angeles.